GREAT WRITERS

Ever since letters were introduced ,man tried to write down his feelings and impressions of the world.This was how literature war grown. World literature is wast well as diverse. Thousands of writers have lived and contributed to the development of the culture , across the world and through the centuries .Many have been forgotten and this blog consists some of them

Thursday, 5 April 2012

KALIDASA

One of the greatest Sanskrit poets that India has ever had, the life history of Kalidas is absolutely fascinating and interesting. Though the exact time of his fame is not known, it is estimated that he survived around the middle of the 4th or 5th century A.D. This is roughly the period of the reign of the famous Chandragupta, the successor of Kumaragupta. An insight into the biography of the great Indian poet Kalidasa provides us with an immense amount of detailed information about the places he traveled and the kind of life he led.

The poems he wrote were usually of epic proportions and were written in classical Sanskrit. His creations were used for fine arts like music and dance. Regarded as an outstanding writer, Kalidasa resided at the palace of Chandragupta in Pataliputra (modern day Patna). He was one of the gems of the court of Chandragupta. According to legends, Kalidasa was blessed with good looks. This attracted a princess with whom he fell in love. Since Kalidas was not too good in intellect and wit, the princess rejected him. He then worshipped Goddess Kali and she blessed him with intellect and wit, thus making him one of the "nine gems" in the court of Chandragupta.

Perhaps the most famous and beautiful work of Kalidasa is the Shakuntalam. It is the second play of Kalidasa after he wrote Malavikagnimitra. The Shakuntalam tells the story of king Dushyant who falls in love with a beautiful girl Shakuntala, who happens to be the daughter of a saint. They get married and lead a happy life until one day, the king is asked to travel somewhere. In his absence, a sage curses Shakuntala as she offends him unknowingly by not acknowledging his presence.

Due to the curse, Dushyant's entire memory is wiped off and he doesn't remember his marriage or Shakuntala. But the sage feels pity for her and gives a solution that he will remember everything if he sees the ring given to her by Dushyant. But she loses the ring one day in the river while bathing. After a series of incidents, a fisherman who finds the ring inside a fish rushes to the king with the ring. The king then recalls everything and rushes to Shakuntala to apologize for his actions. She forgives him and they live happily ever after.

Kalidasa also wrote two epic poems called Kumaarasambhava, which means birth of Kumara and the Raghuvamsha, which means dynasty of Raghu. There are also two lyric poems written by Kalidasa known as Meghadutta that stands for cloud messenger and the Ritusamhara that means description of the seasons. Meghadutta is one of the finest works of Kalidasa in terms of world literature. The beauty of the continuity in flawless Sanskrit is unmatched till date.

It is interesting to observe that the centuries of intellectual darkness in Europe have sometimes coincided with centuries of light in India. The Vedas were composed for the most part before Homer; Kalidasa and his contemporaries lived while Rome was tottering under barbarian assault.

To the scanty and uncertain data of late traditions may be added some information about Kalidasa’s life gathered from his own writings. He mentions his own name only in the prologues to his three plays, and here with a modesty that is charming indeed, yet tantalising. One wishes for a portion of the communicativeness that characterises some of the Indian poets. He speaks in the first person only once, in the verses introductory to his epic poem The Dynasty of Raghu.1 Here also we feel his modesty, and here once more we are balked of details as to his life.

We know from Kalidasa’s writings that he spent at least a part of his life in the city of Ujjain. He refers to Ujjain more than once, and in a manner hardly possible to one who did not know and love the city. Especially in his poem The Cloud-Messenger does he dwell upon the city’s charms, and even bids the cloud make a détour in his long journey lest he should miss making its acquaintance.2

We learn further that Kalidasa travelled widely in India. The fourth canto of The Dynasty of Raghu describes a tour about the whole of India and even into regions which are beyond the borders of a narrowly measured India. It is hard to believe that Kalidasa had not himself made such a “grand tour”; so much of truth there may be in the tradition which sends him on a pilgrimage to Southern India. The thirteenth canto of the same epic and The Cloud-Messenger also describe long journeys over India, for the most part through regions far from Ujjain. It is the mountains which impress him most deeply. His works are full of the Himalayas. Apart from his earliest drama and the slight poem called The Seasons, there is not one of them which is not fairly redolent of mountains. One, The Birth of the War-god, might be said to be all mountains. Nor was it only Himalayan grandeur and sublimity which attracted him; for, as a Hindu critic has acutely observed, he is the only Sanskrit poet who has described a certain flower that grows in Kashmir. The sea interested him less. To him, as to most Hindus, the ocean was a beautiful, terrible barrier, not a highway to adventure. The “sea-belted earth” of which Kalidasa speaks means to him the mainland of India.

Another conclusion that may be certainly drawn from Kalidasa’s writing is this, that he was a man of sound and rather extensive education. He was not indeed a prodigy of learning, like Bhavabhuti in his own country or Milton in England, yet no man could write as he did without hard and intelligent study. To begin with, he had a minutely accurate knowledge of the Sanskrit language, at a time when Sanskrit was to some extent an artificial tongue. Somewhat too much stress is often laid upon this point, as if the writers of the classical period in India were composing in a foreign language. Every writer, especially every poet, composing in any language, writes in what may be called a strange idiom; that is, he does not write as he talks. Yet it is true that the gap between written language and vernacular was wider in Kalidasa’s day than it has often been. The Hindus themselves regard twelve years’ study as requisite for the mastery of the “chief of all sciences, the science of grammar.” That Kalidasa had mastered this science his works bear abundant witness.

He likewise mastered the works on rhetoric and dramatic theory—subjects which Hindu savants have treated with great, if sometimes hair-splitting, ingenuity. The profound and subtle systems of philosophy were also possessed by Kalidasa, and he had some knowledge of astronomy and law.

But it was not only in written books that Kalidasa was deeply read. Rarely has a man walked our earth who observed the phenomena of living nature as accurately as he, though his accuracy was of course that of the poet, not that of the scientist. Much is lost to us who grow up among other animals and plants; yet we can appreciate his “bec-black hair,” his ashoka-tree that “sheds his blossoms in a rain of tears,” his river wearing a sombre veil of mist:

Although her reeds seem hands that clutch the dress

To hide her charms;

his picture of the day-blooming water-lily at sunset:

The water-lily closes, but

With wonderful reluctancy;

As if it troubled her to shut

Her door of welcome to the bee.

The religion of any great poet is always a matter of interest, especially the religion of a Hindu poet; for the Hindus have ever been a deeply and creatively religious people. So far as we can judge. Kalidasa moved among the jarring sects with sympathy for all, fanaticism for none. The dedicatory prayers that introduce his dramas are addressed to Shiva. This is hardly more than a convention, for Shiva is the patron of literature. If one of his epics, The Birth of the War-god, is distinctively Shivaistic, the other, The Dynasty of Raghu, is no less Vishnuite in tendency. If the hymn to Vishnu in The Dynasty of Raghu is an expression of Vedantic monism, the hymn to Brahma in The Birth of the War-god gives equally clear expression to the rival dualism of the Sankhya system. Nor are the Yoga doctrine and Buddhism left without sympathetic mention. We are therefore justified in concluding that Kalidasa was, in matters of religion, what William James would call “healthy-minded,” emphatically not a “sick soul.”

There are certain other impressions of Kalidasa’s life and personality which gradually become convictions in the mind of one who reads and re-reads his poetry, though they are less easily susceptible of exact proof. One feels certain that he was physically handsome, and the handsome Hindu is a wonderfully fine type of manhood. One knows that he possessed a fascination for women, as they in turn fascinated him. One knows that children loved him. One becomes convinced that he never suffered any morbid, soul-shaking experience such as besetting religious doubt brings with it, or the pangs of despised love; that on the contrary he moved among men and women with a serene and godlike tread, neither self-indulgent nor ascetic, with mind and senses ever alert to every form of beauty. We know that his poetry was popular while he lived, and we cannot doubt that his personality was equally attractive, though it is probable that no contemporary knew the full measure of his greatness. For his nature was one of singular balance, equally at home in a splendid court and on a lonely mountain, with men of high and of low degree. Such men are never fully appreciated during life. They continue to grow after they are dead.

Kalidasa left seven works which have come down to us: three dramas, two epics, one elegiac poem, and one descriptive poem. Many other works, including even an astronomical treatise, have been attributed to him; they are certainly not his. Perhaps there was more than one author who bore the name Kalidasa: perhaps certain later writers were more concerned for their work than for personal fame. On the other hand, there is no reason to doubt that the seven recognised works are in truth from Kalidasa’s hand. The only one concerning which there is reasonable room for suspicion is the short poem descriptive of the seasons, and this is fortunately the least important of the seven. Nor is there evidence to show that any considerable poem has been lost, unless it be true that the concluding cantos of one of the epics have perished. We are thus in a fortunate position in reading Kalidasa: we have substantially all that he wrote, and run no risk of ascribing to him any considerable work from another hand.

Of these seven works, four are poetry throughout; the three dramas, like all Sanskrit dramas, are written in prose, with a generous mingling of lyric and descriptive stanzas. The poetry, even in the epics, is stanzaic; no part of it can fairly be compared to English blank verse. Classical Sanskrit verse, so far as structure is concerned, has much in common with familiar Greek and Latin forms: it makes no systematic use of rhyme; it depends for its rhythm not upon accent, but upon quantity. The natural medium of translation into English seems to me to be the rhymed stanza;1 in the present work the rhymed stanza has been used, with a consistency perhaps too rigid, wherever the original is in verse.

Kalidasa’s three dramas bear the names: Malavika and Agnimitra, Urvashi, and Shakuntala. The two epics are The Dynasty of Raghu and The Birth of the War-god. The elegiac poem is called The Cloud-Messenger, and the descriptive poem is entitled The Seasons. It may be well to state briefly the more salient features of the Sanskrit genres to which these works belong.

These drama proved in India, as in other countries, a congenial form to many of the most eminent poets. The Indian drama has a marked individuality, but stands nearer to the modern European theatre than to that of ancient Greece; for the plays, with a very few exceptions, have no religious significance, and deal with love between man and woman. Although tragic elements may be present, a tragic ending is forbidden. Indeed, nothing regarded as disagreeable, such as fighting or even kissing, is permitted on the stage; here Europe may perhaps learn a lesson in taste. Stage properties were few and simple, while particular care was lavished on the music. The female parts were played by women. The plays very rarely have long monologues, even the inevitable prologue being divided between two speakers, but a Hindu audience was tolerant of lyrical digression.

It may be said, though the statement needs qualification in both directions, that the Indian dramas have less action and less individuality in the characters, but more poetical charm than the dramas of modern Europe.

On the whole, Kalidasa was remarkably faithful to the ingenious but somewhat over-elaborate conventions of Indian dramaturgy. His first play, the Malavika and Agnimitra, is entirely conventional in plot. The Shakuntala is transfigured by the character of the heroine. The Urvashi, in spite of detail beauty, marks a distinct decline.

The Dynasty of Raghu and The Birth of the War-god belong to a species of composition which it is not easy to name accurately. The Hindu name kavya has been rendered by artificial epic, épopée savante, Kunstgedicht. It is best perhaps to use the term epic, and to qualify the term by explanation.

The kavyas differ widely from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, epics which resemble the Iliad and Odyssey less in outward form than in their character as truly national poems. The kavya is a narrative poem written in a sophisticated age by a learned poet, who possesses all the resources of an elaborate rhetoric and metric. The subject is drawn from time-honoured mythology. The poem is divided into cantos, written not in blank verse but in stanzas. Several stanza-forms are commonly employed in the same poem, though not in the same canto, except that the concluding verses of a canto are not infrequently written in a metre of more compass than the remainder.

I have called The Cloud-Messenger an elegiac poem, though it would not perhaps meet the test of a rigid definition. The Hindus class it with The Dynasty of Raghu and The Birth of the War-god as a kavya, but this classification simply evidences their embarrassment. In fact, Kalidasa created in The Cloud-Messenger a new genre. No further explanation is needed here, as the entire poem is translated below.

The short descriptive poem called The Seasons has abundant analogues in other literatures, and requires no comment.

It is not possible to fix the chronology of Kalidasa’s writings, yet we are not wholly in the dark. Malavika and Agnimitra was certainly his first drama, almost certainly his first work. It is a reasonable conjecture, though nothing more, that Urvashi was written late, when the poet’s powers were waning. The introductory stanzas of The Dynasty of Raghu suggest that this epic was written before The Birth of the War-god, though the inference is far from certain. Again, it is reasonable to assume that the great works on which Kalidasa’s fame chiefly rests—Shakuntala, The Cloud-Messenger, The Dynasty of Raghu, the first eight cantos of The Birth of the War-god—were composed when he was in the prime of manhood. But as to the succession of these four works we can do little but guess.

Kalidasa’s glory depends primarily upon the quality of his work, yet would be much diminished if he had failed in bulk and variety. In India, more than would be the case in Europe, the extent of his writing is an indication of originality and power; for the poets of the classical period underwent an education that encouraged an exaggerated fastidiousness, and they wrote for a public meticulously critical. Thus the great Bhavabhuti spent his life in constructing three dramas; mighty spirit though he was, he yet suffers from the very scrupulosity of his labour. In this matter, as in others, Kalidasa preserves his intellectual balance and his spiritual initiative: what greatness of soul is required for this, every one knows who has ever had the misfortune to differ in opinion from an intellectual clique.

Le nom de Kâlidâsa domine la poésie indienne et la résume brillamment. Le drame, l’épopée savante, l’élégie attestent aujourd’hui encore la puissance et la souplesse de ce magnifique génie; seul entre les disciples de Sarasvatî [the goddess of eloquence], il a eu le bonheur de produire un chef-d’œuvre vraiment classique, où l’Inde s’admire et où l’humanité se reconnaît. Les applaudissements qui saluèrent la naissance de Çakuntalá à Ujjayinî ont après de longs siècles éclaté d’un bout du monde à l’autre, quand William Jones l’eut révélée à l’Occident. Kâlidâsa a marqué sa place dans cette pléiade étincelante où chaque nom résume une période de l’esprit humain. La série de ces noms forme l’histoire, ou plutôt elle est l’histoire même.1

It is hardly possible to say anything true about Kalidasa’s achievement which is not already contained in this appreciation. Yet one loves to expand the praise, even though realising that the critic is by his very nature a fool. Here there shall at any rate be none of that cold-blooded criticism which imagines itself set above a world-author to appraise and judge, but a generous tribute of affectionate admiration.

The best proof of a poet’s greatness is the inability of men to live without him; in other words, his power to win and hold through centuries the love and admiration of his own people, especially when that people has shown itself capable of high intellectual and spiritual achievement.

For something like fifteen hundred years, Kalidasa has been more widely read in India than any other author who wrote in Sanskrit. There have also been many attempts to express in words the secret of his abiding power: such attempts can never be wholly successful, yet they are not without considerable interest. Thus Bana, a celebrated novelist of the seventh century, has the following lines in some stanzas of poetical criticism which he prefixes to a historical romance:

Where find a soul that does not thrill

In Kalidasa’s verse to meet

The smooth, inevitable lines

Like blossom-clusters, honey-sweet?

A later writer, speaking of Kalidasa and another poet, is more laconic in this alliterative line: Bhaso hasah, Kalidaso vilasah—Bhasa is mirth, Kalidasa is grace.

These two critics see Kalidasa’s grace, his sweetness, his delicate taste, without doing justice to the massive quality without which his poetry could not have survived.

Though Kalidasa has not been as widely appreciated in Europe as he deserves, he is the only Sanskrit poet who can properly be said to have been appreciated at all. Here he must struggle with the truly Himalayan barrier of language. Since there will never be many Europeans, even among the cultivated, who will find it possible to study the intricate Sanskrit language, there remains only one means of presentation. None knows the cruel inadequacy of poetical translation like the translator. He understands better than others can, the significance of the position which Kalidasa has won in Europe. When Sir William Jones first translated the Shakuntala in 1789, his work was enthusiastically received in Europe, and most warmly, as was fitting, by the greatest living poet of Europe. Since that day, as is testified by new translations and by reprints of the old, there have been many thousands who have read at least one of Kalidasa’s works; other thousands have seen it on the stage in Europe and America.

How explain a reputation that maintains itself indefinitely and that conquers a new continent after a lapse of thirteen hundred years? None can explain it, yet certain contributory causes can be named.

No other poet in any land has sung of happy love between man and woman as Kalidasa sang. Every one of his works is a love-poem, however much more it may be. Yet the theme is so infinitely varied that the reader never wearies. If one were to doubt from a study of European literature, comparing the ancient classics with modern works, whether romantic love be the expression of a natural instinct, be not rather a morbid survival of decaying chivalry, he has only to turn to India’s independently growing literature to find the question settled. Kalidasa’s love-poetry rings as true in our ears as it did in his countrymen’s ears fifteen hundred years ago.

It is of love eventually happy, though often struggling for a time against external obstacles, that Kalidasa writes. There is nowhere in his works a trace of that not quite healthy feeling that sometimes assumes the name “modern love.” If it were not so, his poetry could hardly have survived; for happy love, blessed with children, is surely the more fundamental thing. In his drama Urvashi he is ready to change and greatly injure a tragic story, given him by long tradition, in order that a loving pair may not be permanently separated. One apparent exception there is—the story of Rama and Sita in The Dynasty of Raghu. In this case it must be remembered that Rama is an incarnation of Vishnu, and the story of a mighty god incarnate is not to be lightly tampered with.

It is perhaps an inevitable consequence of Kalidasa’s subject that his women appeal more strongly to a modern reader than his men. The man is the more variable phenomenon, and though manly virtues are the same in all countries and centuries, the emphasis has been variously laid. But the true woman seems timeless, universal. I know of no poet, unless it be Shakespeare, who has given the world a group of heroines so individual yet so universal; heroines as true, as tender, as brave as are Indumati, Sita, Parvati, the Yaksha’s bride, and Shakuntala.

Kalidasa could not understand women without understanding children. It would be difficult to find anywhere lovelier pictures of childhood than those in which our poet presents the little Bharata, Ayus, Raghu, Kumara. It is a fact worth noticing that Kalidasa’s children are all boys. Beautiful as his women are, he never does more than glance at a little girl.

Another pervading note of Kalidasa’s writing is his love of external nature. No doubt it is easier for a Hindu, with his almost instinctive belief in reincarnation, to feel that all life, from plant to god, is truly one; yet none, even among the Hindus, has expressed this feeling with such convincing beauty as has Kalidasa. It is hardly true to say that he personifies rivers and mountains and trees; to him they have a conscious individuality as truly and as certainly as animals or men or gods. Fully to appreciate Kalidasa’s poetry one must have spent some weeks at least among wild mountains and forests untouched by man; there the conviction grows that trees and flowers are indeed individuals, fully conscious of a personal life and happy in that life. The return to urban surroundings makes the vision fade; yet the memory remains, like a great love or a glimpse of mystic insight, as an intuitive conviction of a higher truth.

Kalidasa’s knowledge of nature is not only sympathetic, it is also minutely accurate. Not only are the snows and windy music of the Himalayas, the mighty current of the sacred Ganges, his possession; his too are smaller streams and trees and every littlest flower. It is delightful to imagine a meeting between Kalidasa and Darwin. They would have understood each other perfectly; for in each the same kind of imagination worked with the same wealth of observed fact.

I have already hinted at the wonderful balance in Kalidasa’s character, by virtue of which he found himself equally at home in a palace and in a wilderness. I know not with whom to compare him in this; even Shakespeare, for all his magical insight into natural beauty, is primarily a poet of the human heart. That can hardly be said of Kalidasa, nor can it be said that he is primarily a poet of natural beauty. The two characters unite in him, it might almost be said, chemically. The matter which I am clumsily endeavouring to make plain is beautifully epitomised in The Cloud-Messenger. The former half is a description of external nature, yet interwoven with human feeling; the latter half is a picture of a human heart, yet the picture is framed in natural beauty. So exquisitely is the thing done that none can say which half is superior. Of those who read this perfect poem in the original text, some are more moved by the one, some by the other. Kalidasa understood in the fifth century what Europe did not learn until the nineteenth, and even now comprehends only imperfectly: that the world was not made for man, that man reaches his full stature only as he realises the dignity and worth of life that is not human.

That Kalidasa seized this truth is a magnificent tribute to his intellectual power, a quality quite as necessary to great poetry as perfection of form. Poetical fluency is not rare; intellectual grasp is not very uncommon: but the combination has not been found perhaps more than a dozen times since the world began. Because he possessed this harmonious combination, Kalidasa ranks not with Anacreon and Horace and Shelley, but with Sophocles, Vergil, Milton.

He would doubtless have been somewhat bewildered by Wordsworth’s gospel of nature. “The world is too much with us,” we can fancy him repeating. “How can the world, the beautiful human world, be too much with us? How can sympathy with one form of life do other than vivify our sympathy with other forms of life?”

It remains to say what can be said in a foreign language of Kalidasa’s style. We have seen that he had a formal and systematic education; in this respect he is rather to be compared with Milton and Tennyson than with Shakespeare or Burns. He was completely master of his learning. In an age and a country which reprobated carelessness but were tolerant of pedantry, he held the scales with a wonderfully even hand, never heedless and never indulging in the elaborate trifling with Sanskrit diction which repels the reader from much of Indian literature. It is true that some western critics have spoken of his disfiguring concerts and puerile plays on words. One can only wonder whether these critics have ever read Elizabethan literature; for Kalidasa’s style is far less obnoxious to such condemnation than Shakespeare’s. That he had a rich and glowing imagination, “excelling in metaphor,” as the Hindus themselves affirm, is indeed true; that he may, both in youth and age, have written lines which would not have passed his scrutiny in the vigour of manhood, it is not worth while to deny: yet the total effect left by his poetry is one of extraordinary sureness and delicacy of taste. This is scarcely a matter for argument; a reader can do no more than state his own subjective impression, though he is glad to find that impression confirmed by the unanimous authority of fifty generations of Hindus, surely the most competent judges on such a point.

Analysis of Kalidasa’s writings might easily be continued, but analysis can never explain life. The only real criticism is subjective. We know that Kalidasa is a very great poet, because the world has not been able to leave him alone.

Tuesday, 3 April 2012

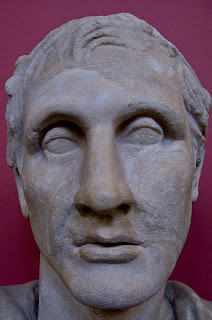

PLUTARCH

Pultarch lived a long and fruitful life with his wife and family in the little Greek town of Chaeronea. For many years Plutarch served as one of the two priests at the temple of Apollo at Delphi (the site of the famous Delphic Oracle) twenty miles from his home. By his writings and lectures Plutarch became a celebrity in the Roman empire, yet he continued to reside where he was born, and actively participated in local affairs, even serving as mayor. At his country estate, guests from all over the empire congregated for serious conversation, presided over by Plutarch in his marble chair. Many of these dialogues were recorded and published, and the78 essays and other works which have survived are now known collectively as the Moralia.

After the horrors of Nero and Domitian, and the partisan passions of civil war, Rome was ready for some gentle enlightenment from the priest of Apollo. Plutarch's essays and his lectures established him as a leading thinker in the Roman empire's golden age: the reigns of Nerva, Trajan, and Hadrian.

The study and judgment of lives was always of paramount importance for Plutarch. In the Moralia, Plutarch expresses a belief in reincarnation. 2 His letter of consolation to his wife, after the death of their two-year-old daughter, gives us a glimpse of his philosophy:

"The soul, being eternal, after death is like a caged bird that has been released. If it has been a long time in the body, and has become tame by many affairs and long habit, the soul will immediately take another body and once again become involved in the troubles of the world. The worst thing about old age is that the soul's memory of the other world grows dim, while at the same time its attachment to things of this world becomes so strong that the soul tends to retain the form that it had in the body. But that soul which remains only a short time within a body, until liberated by the higher powers, quickly recovers its fire and goes on to higher things."

Once his judgment had been seasoned by maturity, and his writing skill by long practice on his essays, Plutarch commenced the composition of his immortal Parallel Lives. The language Plutarch wrote in was Attic Greek, which was well-known to the educated class in the Roman Empire. The installments of this ponderous work (what has survived totals approximately 800,000 words, ~1300 pages of fine print) were sent to Sosius Senecio, who was consul of Rome during the years 99, 102, and 107 A.D. Through Sosius, Plutarch had the ear of the emperor Trajan and the means to have many copies of his work made.

Plutarch's plan in the Lives was to pair a philosophical biography of a famous Roman with one of a Greek who was comparable in some way. A short essay of comparison follows most of the pairs of lives. His announced intention was not to write a chronicle of great historical events, but rather to examine the character of great men, as a lesson for the living. Throughout the Lives, Plutarch pauses to deliver penetrating observations on human nature as illustrated by his subjects, so it is difficult to classify the Lives as history, biography, or philosophy. These timeless studies of humanity are truly in a class by themselves.

Plutarch's Greek heroes had been dead for at least 300 years by the time he wrote their lives (circa 100 A.D.). Plutarch therefore had to rely on old manuscripts, many of which are no longer available. But even the legends of antiquity may be smelted by the power of reason to yield some insight, as Plutarch assures us at the beginning of his life of Theseus. It is up to the reader to use this divine spark to intuit the truth from the details by means of the power of abstraction, which is "passing from a plurality of perceptions to a unity gathered together by reason." (Plato, Phaedrus 249). Plutarch himself had no faith in the accuracy of even the purportedly factual materials he had to work with, as is evident from this comment in his life of Pericles:

"It is so hard to find out the truth of anything by looking at the record of the past. The process of time obscures the truth of former times, and even contemporaneous writers disguise and twist the truth out of malice or flattery."

The Romans loved the Lives, and enough copies were written out over the next centuries so that a copy of most of the lives managed to survive the coming Dark Ages of dogma and neglect. However, many lives which appear in a list of his writings, such as those of Hercules, Scipio Africanus, and Epaminondas, have not been found and may be lost forever.

At the beginning of the Italian Renaissance, it was the rediscovery of Plutarch's Lives that stimulated popular interest in the classics. Epitomes, which hit the highlights of the best stories and were written in Tuscan and other local dialects, circulated as popular literature. Captains and merchants took time to read the popularized Plutarch for its practical wisdom, and thus the Lives not only survived, but became a huge hit all over Europe during the Renaissance. 3 "We dunces would have been lost if this book had not raised us out of the dirt," said Montaigne of the first French edition (1559). 4 C.S. Lewis concludes that in Elizabethan England, "Plutarch's Lives built the heroic ideal of the Elizabethan age." 5 Sir Thomas North prepared the first English edition of Plutarch's Lives in 1579, and Shakespeare borrowed heavily from it. 6 In 1683, a team of translators headed by John Dryden authored a complete translation from the original Greek (North had translated from Amyot's French edition).

Great souls have found comfort in Plutarch's wisdom. Beethoven, growing deaf, wrote in 1801: "I have often cursed my Creator and my existence. Plutarch has shown me the path of resignation. If it is at all possible, I will bid defiance to my fate, though I feel that as long as I live there will be moments when I shall be God's most unhappy creature ... Resignation, what a wretched resource! Yet it is all that is left to me." Facing death in Khartoum, General Gordon took time to note: "Certainly I would make Plutarch's Lives a handbook for our young officers. It is worth any number of 'Arts of War' or 'Minor Tactics'." 7 Ralph Waldo Emerson called the Lives "a bible for heroes." 8

By the twentieth century, however, Plutarch's popularity began to fade. Professional classicists produced no revitalizing new edition of the Lives in modern English, and by the 1990's, classical studies had so declined in popularity that a riot at Stanford University featured thousands of the top students in the United States chanting the battlecry of the new creed, Diversity: "Hey Hey, Ho Ho, Western Culture's Got To Go." Plutarch's heroes had no place in their brave new world of gray equality, populated by puppets of money, resentful of eminence.

Moreover, all discrimination between good and bad was actively suppressed among the intelligentsia. In the words of Simone Weil: "The essential characteristic of the first half of the twentieth century is the growing weakness, and almost the disappearance, of the idea of value. ... But above all [those responsible were] the writers who were the guardians of the treasure that has been lost; and some of them now take pride in having lost it." 9

Another cause for Plutarch's loss of popularity was that reading skills declined generally with the advent more seductive entertainment such as television and Nintendo games, and the decline of public schools. Plutarch's elaborate sentence structure and long digressions, preserved in the Dryden edition, are a challenge to modern young readers of English, who, if they read at all, require a pruned-down text that gets to the point.

As classics departments continue to close, embattled scholars demand cramdown Greek grammar for all, and Greek drama in the original. The best has indeed become the enemy of the good. Scholastic diligence has produced such a dense cloud of ink that the ancient light grows dim, and so, at the end of the twentieth century, the cycle of Plutarch's popularity has reached its perigee.

But Plutarch will always come back, as he has after other dark ages. We find Plutarch surprisingly relevant today because nothing really has changed in human nature over the nineteen centuries since Plutarch wrote. As the greatest English thinker, Samuel Johnson, put it: "... we are all prompted by the same motives, all deceived by the same fallacies, all animated by hope, obstructed by danger, entangled by desire, and seduced by pleasure." The Rambler, No. 60. And we all need heroic examples to show us the way.

There is a definite effect on readers of these ancient stories. Emerson said: "We cannot read Plutarch without a tingling of the blood; and I accept the saying of the Chinese Mencius: 'A sage is the instructor of a hundred ages. When the manners of Loo are heard of, the stupid become intelligent, and the wavering, determined.' " 10 The spiritually inductive power of Plutarch's heroes, apart from Plutarch's own skill at sketching character and imparting wisdom, may explain the perennial appeal of the Lives.

To the biographies of his heroes, Plutarch brought a master's eye for the essence. Impressionist artists and poets are not to be faulted for failing to record every detail of their subjects with scrupulous fidelity, and likewise we should recognize that a deft sentence from Plutarch means more than volumes from minor scribes. Historical details are only incidental to the character of Plutarch's subjects. He clearly disclaims any pretensions to being a historian at the beginning of his life of Alexander: "My intention is not to write histories, but lives." The difference between Plutarch and a dry chronicle of the times is the difference between a cake and a pile of ingredients, understanding and knowledge, a person and a corpse.

It is this difference which makes a classic. Plutarch transcends the historical subjects he deals with and the period he wrote in. As Ben Jonson said of Shakespeare, we may say of Plutarch: "He was not of

VIRGIL

Publius Vergilius Maro was a classical Roman poet, best known for three major works—the Bucolics (or Eclogues), the Georgics, and the Aeneid—although several minor poems are also attributed to him. The son of a farmer in northern Italy, Virgil came to be regarded as one of Rome's greatest poets; his Aeneid as Rome's national epic.

Over the past 300 years, much of Virgil’s long-standard ancient biography, based on hearsay and legends, has been challenged. (Vergil with an e is the classical Roman spelling, normal in Germany, and thence adopted by some in the United Kingdom and the United States, contrary to traditional literary usage). These ancient biographies include much material that has been believed only because it was applied to Virgil. Romans and Italians after his death attributed many myths to Virgil's tomb, for example, which is located near Naples, contending that the cave in which he was buried was carved out from the supernatural power of Virgil's gaze. Now biographers try to piece together Virgil's life from his own writings and the writings of his contemporaries. Virgil almost without a biography, without the lavish myths, turns out to be no less great a poet than he was before.

His earliest poetry reveals a formidable literary training; legend contends that he was sent to Rome at the age of 5 to study rhetoric, medicine, philosophy, and astronomy. The rustic tragedies of his Bucolics 1 and 9 are the stuff of life in Italy during the First Triumvirate (Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus) and the Second Triumvirate (Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian) and not necessarily autobiographical; nevertheless, they show Virgil's concerns in his early career. Already in Bucolic 1 Virgil writes with admiration of the young Octavian, whom Cicero at the same time dismissed as a teenage butcher. How Virgil actually came into contact with Maecenas, early Octavian’s adviser in matters of cultural politics, no one knows. About 38 B.C., however, Virgil was already well enough placed to be able to introduce Horace to Maecenas (Horace, Satires 1.6.54f.), and perhaps in the spring of 37 B.C. both Virgil and Horace accompanied Maecenas and various other public figures on their journey from Rome to Brundisium (Horace, Satires 1.5). The Bucolics were a huge popular success: the poems were performed on-stage, and more than four hundred years after publication they were recited in the streets of Rome by Christian priests who should have been reciting psalms. This success made Virgil’s next poetic undertaking a matter of public moment. He says (Georgics 3.41) that the Georgics were “your ungentle orders, Maecenas.” “Ungentle,” though, is typically elusive: does Virgil mean that the orders were stern or that the subject-matter of the new poem was not gentle? “Orders” is a crude way of rendering iussa, which Peter White says in Promised Verse (1993) is a word used for many kinds of literary suggestions, invitations, or requests. The text does not suggest that Virgil is the willing (or unwilling) servant of a vast and coercive propaganda machine. Maecenas had seven years to wait for the Georgics, and the poem reflects the political changes of the period of composition. Octavian stopped near Naples for four days in 29 B.C., while returning to celebrate his triumph over Antony and Cleopatra, in order to listen to Virgil and Maecenas recite the newly completed Georgics.

Virgil had become a major national figure, as well as a rich man: his estate came to be worth twenty-five times the property qualification of a Roman knight, but crude cash handouts in properly behaved circles at Rome were entirely unthinkable, and it would be unjustified cynicism to suppose that Maecenas secured the poet’s loyalty with a series of handouts. The date Virgil actually began the Aeneid is equally uncertain: the proemium to the third Georgic (verses 21-39) suggests that he was thinking of writing an epic long before he actually began it, though he may not even have finished the Georgics before beginning the Aeneid. Virgil died in 19 B.C., before the Aeneid was altogether finished, and formal imperfections have indeed been detected. Just as Propertius was excited by the thought of the forthcoming epic (2.34.61-66), Augustus was urgent to hear something of it before “publication” of the whole; that Virgil read the imperial family three books (2, 4, and 6, though that is not certain) in 22 B.C. seems probable. It is related that Virgil wanted to spend three years in Greece to perfect the text, but Augustus, on his way back from the East, met him at Athens, and the poet decided to return to Italy with Augustus. Heatstroke incurred at Megara led to Virgil’s death at Brindisium. Some of this sequence of events may be true; there are objections to almost all of it, however, and various ancient accounts of what Virgil had laid down in his will as to what should be done in case he died with the poem unfinished are strikingly inconsistent. The tale that Augustus saw to the posthumous publication of the epic that the poet himself had wished should be burned if he could not see to its completion is moving but may well be rather a long way from the facts.

In Virgil’s hands, pastoral turned into a poetic genre in which the author could use humble characters to talk about public figures and current affairs. Because shepherds are the poet-musicians of the countryside, Virgil can also talk about poetry on their lips and can lard their conversation with poetic allusions to predecessors and contemporaries, both Greek and Latin. He does so notably in Eclogues 6 (Gallus, v. 64) and 10 (Gallus the dedicatee); that ten fragmentary lines of Cornelius Gallus’s (rather disappointing) poetry have now been discovered on a scrap of papyrus has not helped to clarify the situation. Particularly in the prologue to Eclogue 6, Virgil is at pains to underline the modesty of pastoral poetry: didactic and epic were definite steps up the hierarchy of poetic dignity, but humble pastoral turns out to be a singularly pliable literary form: its meter is epic (hexameter); its theme (love, often) suggests elegy or lyric; its use of refrains is decidedly lyric; and the dialogues, contests, and touches of jolly fun suggest mime. Virgil’s pastoral poetry, however, is not just a literary construct, inasmuch as there are striking touches of realism in the descriptions of country life (1.34f., 3.94ff.), and the names of rustic deities and their festivals (3.76f., 5.35, 10.94) suggest familiar Italy and not the distant world of Theocritus, though the landscape, however important an element it is in the various poems as the setting for personal love and public tragedy, and as a consolation for both, never attains that degree of specificity that makes the descriptions in the works of Lucretius and in the Georgics so fascinating at times.

The proemium of the first Georgic announces the subject matter of all four books of the Georgics: crops, vines, cattle, and bees. It is a didactic poem, then, about agriculture, but that is something different from a poem intended to teach its readers how to farm—a fundamental distinction that has caused much confusion and needs to be cleared up. The imagined audience of the Georgics is indeed composed of farmers (whom Virgil addresses, for example, at 1.100), but the intended readership of this same poem is necessarily at a far higher cultural level. That is not to say that farmers could not read. They could and did, and a little bit is known about the rough manuals that existed for them, but the literary texture of the Georgics is exceptionally dense and complicated, and to get into them to any depth, the reader (ancient or modern) needs ample grounding in a great body of Greek literature, both prose and verse, and not all of it, by any means, about farming. There is a fair bit of apparently instructional material in the poem, but it is unsystematic, incomplete, and at times positively inaccurate, as later Roman writers realized. Nor is it quite clear about what sort of farm Virgil is writing; indeed, he may actually have preferred to leave the issue open. Usually he writes about the smallholder, the farmer who does most of the work himself: that sort of agriculture had most appeal to poet and reader, and it also rested on a long poetic tradition, going back to Hesiod’s Works and Days. But just sometimes (1.286; possibly 1.343, 2.230, 259) he writes about slaves, and occasionally too he talks about agricultural techniques and situations only appropriate to a large-scale landholder (2.177-258: only on a large farm are there many varieties of soil; 1.49: barns full of grain). So Virgil writes about farming, but not for farmers, and in a precise historical context: he began during the time when the Civil War had wrought great damage to farming in Italy—plunder and destruction, conscription, confiscation, redistribution, and neglect of land while its owners were on active service; all played harmful roles. Sextus Pompeius, son of Pompey the Great, had blocked much of the regular grain supply from Egypt, and famine was a serious prospect. It is too easy to say that Virgil—once Sextus Pompeius was defeated (3 September 36 B.C.) and it became more likely that Octavian, not Antony, would become undisputed master of Italy—began to map out a poetic design for a mass return to the land on the basis of traditional smallholdings, in keeping with an official policy (of sorts) of agricultural renewal. There is no historical evidence for such a policy, though the beneficent effects of peace (after 31 B.C., that is) upon farming were recognized. A return to an agricultural economy based upon smallholdings made no sort of practical sense, but Virgil wrote at a time when “restoration” and “return” were notions dear to Octavian and his advisers (for example, Maecenas and Cicero‘s old friend Atticus). The spirit of traditional farming (as symbolized by the figure of the elder Cato, both as he had spoken and written and as Cicero had presented him in his “On Old Age”) was a very different matter from the long-gone reality. As a moral and ethical ideal, “the farmers of old” and a style of life that could credibly be attributed to them were eminently suitable and attractive matter for a didactic poem—and not only formally didactic, but also widely and brilliantly descriptive. Not, that is, just “how to” but also “see how it is.” That way of looking at nature had come to Virgil, above all, from Lucretius, whose Epicurean didactic poem had appeared when he was sixteen or so years old: to Lucretius, minute observation of the visible world served by analogy to explain what the eye could not see. The infinite poetic possibilities of the detailed observation of nature were perfectly suited to Virgil’s talents and purpose, as becomes clear to anyone who reads, for instance, the list of weather signs, (Geo. 1.351-423). Even though there survive two Greek texts and two Latin translations used by Virgil, one would never imagine that much of this wonderful precision is literary and derivative. Just how well Virgil himself knew the details of farmwork is not clear: scholars learn more and more both about his Greek sources, in prose and verse, and about the mass of detail compatible with prose farming manuals in Latin of such writers as Cato, Varro, Columella, and Palladius. The Georgics are brilliant as didactic poetry precisely because they are so admirable in their descriptions. When Virgil from time to time abandons the (relatively) narrow detail of the matter in hand to turn to an excursus (digression), his reason is not that nature and farming are so dry and dull that they need relief or alleviation but that the poet is well aware that a change of tone and perspective is called for. The digressions comment on and illustrate in ampler terms the more strictly didactic text; their role in some ways is not unlike that of the choruses of Greek tragedy.

Virgil, in the course of his literary career, undertook steadily larger projects, moving also up the scale of stylistic and generic grandeur. To say that this progression was calculated and inevitable is too easy; already at the time of Bucolics, Virgil was thinking about epic (6.1ff.), and when he was writing Aeneid, he still remembered Bucolics (7.483ff.). Alongside the formal and perfect growth of his literary career, Virgil’s relationship with Augustus developed. That an ancient life says that Augustus proposed the topic of the Aeneid to Virgil does not matter. More important are the repeated observations, made by ancient readers of the epic to whom a clear perception of rhetorical structure and intent came far more naturally than it does today, that Virgil’s purpose was to relate (and praise) the origin of the city of Rome and of Augustus’s own family. That from the late second century B.C. onward the family of the Julii Caesares claimed descent from Aeneas is central to Virgil’s choice of the story of Aeneas as the plot for his epic. Julius Caesar made much of this genealogy in the image that his publicity projected, and his great-nephew and adopted son Octavian followed this lead—in art, ritual, and coins. However unwelcome such facts are to most modern students of Virgil, who is normally seen as a poet of doubt, suffering, and criticism of Roman and imperial values, they do remain facts; some further details can be found in Vergilius, 32 (1986). The crude question “But did Augustus tell Virgil to write the Aeneid? “ is best not asked, not least because Augustus and Maecenas in their best years did not do things that way. Augustus’s repeated involvement in the development and publication of the poem (fragments of the correspondence between poet and emperor are actually available) has inevitably some bearing on modern readers’ judgment if they look at the epic at least in part in its historical context. Of course, a reading of the epic in terms of a modern, liberal, antimilitarist ethic will come up with wildly different answers; indeed, much current discussion of the Aeneid is violently politicized.

It is necessary to look at the Aeneid in terms that did, demonstrably, make sense in Virgil’s own time: that is not to deny that today’s Virgil too has a right to exist, but it is best to get to know the text really well before deciding not only what its moral issues are but also what stand the poet takes on them. For there is no room for doubt: while Virgil tells a remarkable story (and St. Augustine as a schoolboy was fascinated by books 2 and 4, as he says in Confessions, book 1, ch. 13), which army officers carried on campaign, schoolboys wrote on the walls of Pompeii, and crowds heard read in the theater, the Aeneid is also a vehicle for profound meditations on the human condition, on character and moral judgment, on war and peace, on conflict of duties, on the state, on the gods, and on Roman history; see St. Augustine’s reading of Aeneid in his City of God.

Ovid

Ovid ws from a rich family that lived near Rome.Ovid's full name was Pubilus Ovidius Naso .His father wanted him to became a lawyer , but Ovid decided to be a poet .He published his first book of poetry about 18 B.C .,when he was 25 years old .it was called the 'AMORES ', OR lOVE POEMS .This book was remarkable,becuase in those days,,peopl;e were not allowed to write abou of love outside of marriage,and Ovid did just that.

Ovid's second book was also remarkable,but in a differwent way.He wrote the Metamorphoses,or the changes,hich he published probably publishedabout8 B.C.,when he was 35 years old .This is a long poem telling lots of short stories about the changes in the world from the time of creation to the death of Julius Ceaser.It tells nearly every story from Greek Mythology that we know -in fact ,many Greek stories are know today mainly becuase they are in Metamorphoses.

MENANDER

Menander is the most famous writer of what is described as Athenian nwew comedy.Unlike the classical writers who wrote mythical pots or political comentry,Mender was a social writer..He chose aspects of daily life as topics for his plays with happy endings and themes.

Menander wrote about stern fathers, young lovers, crafty slaves,and other people who were part of social fabric of the social fabric of Greece in those days.The every day life of his countrymen,as well as the manners and characteristics of ordinary people were at the heart of his stories.His characters spoke in the contemporary dialect,and concerned themselves not with the great myths of the past ,but rather,with the everyday affairs of the people of Athens.

By the end of his career ,Menander had written more than 100 plays and had won 8 victories at Athenian dramatic festivals.Menander's plays were held in high esteem in the literature of western Europe for over 800 years.At some point ,however ,his manuscripts were lost or destroyed and what we now know of the poet is based primarily on ancient reports,a few manuscripts which have been recovered in the last 100 years, and adaptations by the Roman playwrights.

Monday, 19 March 2012

PHILEMON

Philemon was a poet of the Athenian New Comedy.He was noted for his neatly contrived plots , vivid description ,dramatic surprises,and moralizing .by 328.b.c, he was producing plays in Athens ,where he eventually became a citizen .Of the 97 comedies he wrote.some 60 titles survive in Greek fragments and Latin adaptations.Philemon was contemporary and rival for Menander ,whom he is said to have vanquished in poetical contests.Of the ninety-seven plays which he is said to have composed, the titles of fifty-seven and considerable fragments have been preserved. Some of these may have been the work of his son, the younger Philemon, who is said to have composed fifty-four comedies. The Merchant and The Treasure of Philemon were the originals respectively of the Mercator and Trinummus of Plautus. The fragments preserved by Stobaeus, Athenaeus and other writers contain much wit and good sense. Quintilian assigned the second place among the poets of the New Comedy to Philemon, and Apuleius, who had a high opinion of him, has drawn a comparison between him and Menander.

As a boy, Philemon spent many summers at his grandpa's house in Bristol, Rhode Island, where he fell in love with boats and the sea. After a four-year Navy stint in Japan, he moved back to Rhode Island. When he wasn't working on the development of downtown Providence, the waterfront of Newport, or the boat basin on Nantucket, he spent his time sailing, clamming, and riding the waves in his dory, the Dawn Treader. He even spent a year living on an old ferryboat moored in Providence Harbor.

Currently, Philemon splits his time between the city and the country. He can be found at home in the heart of Boston's South End (in a brownstone he redesigned) or out in the charming country town of Princeton, Massachusetts. He lives with his wife, Judy Sue, and his two dogs, Rufina and Giotto. Wherever he is, Philemon enjoys cooking and eating and spending time with friends. (Rufina and Giotto love his leftovers!)

He must have enjoyed remarkable popularity, for he repeatedly won victories over his younger contemporary and rival Menander, whose delicate wit was apparently less to the taste of the Athenians of the time than Philemon's more showy comedy. To later times his successes over Menander were so unintelligible as to be ascribed to the influence of malice and intrigue.

Except for a short sojourn in Egypt with Ptolemy II Philadelphus, he passed his life at Athens. He there died, nearly a hundred years old, but with mental vigour unimpaired, about the year 262 BC, according to the story, at the moment of his being crowned on the stage.

Greek poet of the New Comedy, was born at Soli in Cilicia, or at Syracuse. He settled at Athens early in life, and his first play was produced in 330. He was a contemporary and rival of Menander, whom he frequently vanquished in poetical contests. Posterity reversed the verdict and attributed Philemon's successes to unfair influence. He made a journey to the east, and resided at the court of Ptolemy, king of Egypt, for some time. Plutarch (De Cohibenda Ira, 9) relates that on his journey he was driven by a storm to Cyrene, and fell into the hands of its king Magas, whom he had formerly satirized. Magas treated him with contempt, and finally dismissed him with a present of toys. Various accounts of his death are given; a violent outburst of laughter, excess of joy at a dramatic victory, or a peaceful end while engaged in composing his last work (Apuleius, Florida, 16; Lucian, Macrob. 25; Plutarch, An Seni, p. 725). Of the ninety-seven plays which he is said to have composed, the titles of fifty-seven and considerable fragments have been preserved. Some of these may have been the work of his son, the younger Philemon, who is said to have composed fifty-four comedies. The Merchant and The Treasure of Philemon were the originals respectively of the Mercator and Trinummus of Plautus. The fragments preserved by Stobaeus, Athenaeus and other writers contain much wit and good sense. Quintilian (Instit x. 1, 72) assigned the second place among the poets of the New Comedy to Philemon, and Apuleius, who had a high opinion of him, has drawn a comparison between him and Menander.

HOMER

Homer lived around 700.b.c in Greece.The exact place were he lived is not known correctly.People told he was blind ,but we don't know weather it is right or wrong.When Homer was born, the Greek had just recently learned how to learn the alphabets from the Phoenicians.Homer used the alphabet to write down too long epic poems known'Odyssey'.

The lliad and Odyssey contain incomparable tales of the Torjan war, brave Achilles, Ulysses and Penelope, the Sirens, the CYCLOPS, the beautiful Helen Of Troy, and the angry gods.They are perhaps the most influential works in the history of western literature.These two poems, written nearly 3,000 years ago, have captured the heats of generation through out of the world.

Homer didn't make up these stories ,or even the words ,himself.Poets or Bards had been going around Greece telling these stories for hundred's of years .But Homer wrote them down ,polished them ,and gave them their final form,and therein lies his greatness.

Quote About Homer:

"Homer and Hesiod have ascribed to the gods all things that are a shame and a disgrace among mortals, stealing and adulteries and deceiving on one another."

Many Greek and Latin authors were consciously influenced by Homer's language, and several people tried to emulate the Homeric heroes (e.g., Agesilaus II and Alexander the Great). In Egypt, he received divine honors.

His most important influence, however, must be sought somewhere else. Unlike contemporary sources from other cultures, Homer's poems are more or less "objective". An Egyptian text leaves no doubt that the enemy of pharaoh are evil impersonated. Homer, on the other hand, offers a balanced judgment of the Trojans and Greeks. This objectivity is not unique in the ancient world -Babylonian chronicles have no difficulty in admitting defeats of Babylonian rulers- but it is rare in ancient literature. Through the Histories by Herodotus of Halicarnassus, this may be the Poet's greatest legacy to western civilization.

Several other poems were attributed to Homer, some of them belonging to the Epic Cycle. The Hymns have survived.

It is impossible to pin down with any certainty when Homer lived. Eratosthenes gives the traditional date of 1184 BC for the end of the Trojan War, the semi-mythical event which forms the basis for the Iliad. The great Greek historian Herodotus put the date at 1250 BC. These dates were arrived at in a very approximate manner; Greek historians usually used genealogy and estimation when trying to find the dates for events in the distant past. But Greek historians were far less certain about the dates for Homer's life. Some said he was a contemporary of the events of the Iliad, while others placed him sixty or a hundred or several hundred years afterward. Herodotus estimated that Homer lived and wrote in the ninth century BC. He almost certainly lived in one of the Greek city-states in Asia Minor. All of the traditional sources say that he was blind.

Over the course of millennia of scholarly speculation, prevailing theories about Homer and his relationship to his work have had time to change and change again. At various times over the centuries, scholars have suggested that he was only a transmitter, or that he never existed, and the epics attributed to him were the patchwork effort of generations of bards. Modern scholars, however, tend to accept that the Iliad and the Odyssey are more than amalgams handed down from antiquity, and that there was in fact a great poet who had a hand in creating these epics in the forms we know today. Current scholarship holds that Homer was a great bard who lived between the eighth and seventh centuries BC. Although there is little doubt that Homer inherited a massive amount of material from generations of bards before him, most scholars believe now that Homer was an innovator and an original artist as well as a transmitter. Writing probably played a role in the composition of his great poems. Current theories depict Homer as a master of oral poetry who used the new invention of writing to aid him in composing epics on a grander scale than had ever been done before. There are signs in the Iliad that might suggest unfinished revision; these massive projects may have been reworked again and again over the course of the poet's whole life. A performer as well as a poet, Homer may have composed the poems through a mixture of utilizing old material, writing and revising, and oral improvisation.

Little can be known with certainty. But even though the details of Homer's life remain?and probably will always remain?an enigma, his great epics come down to us intact. His works have formed a foundation for all the Western literature that has followed, and his characters and stories have had an impact on three thousand years' worth of readers. Facts about the poet's life can do little to add to that legacy. Legend says that as a child, Alexander the Great slept with a copy of the Iliad under his pillow?and the fact that Alexander was neither the first nor the last boy to do so says more about Homer's genius than any biography could, no matter how detailed or complete.

Evidence from the epics

This lack of any historical record of Homer's life leaves only what can be taken from the poems themselves. On this task many scholars have attempted to draw conclusions about Homer, often without acceptable results.

The setting of the Iliad is the plain of Troy (an ancient Greek city) and its immediate surroundings. Details of the land are so precise that it is not feasible to suppose that their author created them out of his imagination. To be sure, there is the objection that not all of the poem's action can be made to fit the present-day lands.

In the Odyssey the situation is in many respects quite different. The poet demonstrates that he knew the western Greek island of Ithaca (where the second half of the epic takes place) as well as the poet of the Iliad knew the plain of Troy. The Odyssey, however, also extends over many strange, distant lands, as Odysseus's homeward voyage from Troy to his native Ithaca is transformed into a bizarre sea-wandering adventure.

Perhaps misled by the accuracy with which the Trojan plain is described in the Iliad and the island of Ithaca is pictured in the Odyssey, various modern commentators have tried to impose the same realism on Odysseus's astonishing voyage, selecting actual sites in the western Mediterranean Sea for his adventures. The true situation must be that the Homer of the Odyssey had never visited that part of the ancient world, but he had instead listened to the stories of returning Ionian sailors who explored the western seas during the seventh century B.C.E.

Theory of two authors

That the author of the Iliad was not the same as the author of these fantastic tales in the Odyssey is arguable on several levels. The two epics belong to different literary types: the Iliad is essentially dramatic in its confrontation of opposing warriors who converse like the actors in a tragedy (a play with struggle and disappointment), while the Odyssey is cast as a novel narrated in more everyday human speech. In their physical structure, also, the two epics display an equally obvious difference: the Odyssey is composed in six distinct parts of four chapters ("books") each, whereas the Iliad moves unbrokenly forward in its tightly woven plot.

Readers who examine psychological qualities see in the two works some distinctly different human responses and behavioral attitudes. For example, the Iliad voices admiration for the beauty and speed of horses, while the Odyssey shows no interest in these animals. The Iliad dismisses dogs as mere

Homer.

Reproduced by permission of

Archive Photos, Inc.

scavengers, while the poet of the Odyssey reveals a modern sympathy for Odysseus's faithful old hound, Argos.

The strongest argument for separating the two poems is the chronology, or dating, of some of the facts in the pieces. In the Iliad the Phoenicians are praised as skilled craftsmen working in metal, and as weavers of elaborate, much-prized garments. In contrast, Greek feelings toward the Phoenicians have undergone a drastic change in the Odyssey. Although they are still regarded as clever craftsmen, the Phoenicians are also described as "tricksters," reflecting the invasion of Phoenecian commerce into Greek markets in the seventh century B.C.E.

Oral composition;

One thing, however, is certain: both epics were created without writing sources. Between the decline of Mycenaean and the emergence of classical Greek civilizations—which is to say, from the late twelfth to the mid-eighth century B.C.E. —the inhabitants of the Greek lands had not yet acquired from the easternmost shore of the Mediterranean the familiarity with Phoenician alphabetic writing that would lead to classical Greek literacy (and in turn, Etruscan, Roman, and modern European literacy). Therefore it could be concluded that the epics must have been created either before the end of the eighth century B.C.E. or so shortly afterwards that the use of alphabetic writing had not yet been developed sufficiently to record long pieces of writing. It is this illiterate (unable to read or write) environment that explains the absence of all historical record of the author's two great epics.

it is probable that Homer's name was applied to two individuals differing in style and artistic accomplishment, born perhaps as much as a century apart, but practicing the same traditional craft of oral composition and recitation (to read out loud). Although each became known as "Homer," it may be (as one ancient source says) that "homros" was a word for a blind man and so came to be used generically to refer to the old and often sightless wandering reciters of heroic legends. Thus there could have been many Homers.

The two epics Homer is generally regarded as writing, however, have been as highly prized in modern as in ancient times for their vividness of expression, their keenness of personal characterization, and their lasting interest, whether in narration of action or in animated dramatic dialogue.

Other works ;

Later Greek times credited Homer with the composition of a group of comparatively short "hymns" (songs of praise) addressed to various gods, of which twenty-three have survived. With a closer look, however, only one or two of these, at most, can be the work of the poet of the two great epics. The epic "The Battle of the Frogs and Mice" has been preserved but adds nothing to Homer's reputation. Several other epic poems of considerable length— The Cypria, The Little Iliad, The Phocais, The Thebais, and The Capture of Oichalia —were also credited to Homer in classical times.

The simple truth seems to be that the name Homer was not so much that of a single individual but an entire school of poets flourishing on the west coast of Asia Minor (today, the area of Turkey). Unfortunately, we will probably never know for sure, since during this period the art of writing had not been sufficiently developed by the Greeks to permit historical records to be compiled or literary compositions to be written down.

Essential Facts;

Although there are multiple accounts of Homer’s origins and life, scholars have been unable to validate the historical accuracy of any of them.

Homer’s reputation in the classical period reached its apex when a religious following of the poet emerged. These followers believed Homer to have been divinely inspired in his writing.

For many centuries, Homer’s work remained somewhat obscure. It was only during the neoclassical movement of the Renaissance that his writing regained prominence.

The Trojan War, which provides the basis for The Iliad, may not have happened. While it is probably based on an actual war, many believe Homer’s account of it to be a fictionalization.

The Coen Brother’s 2000 film, O Brother, Where Art Thou, is a retelling of Homer’s The Odyssey set in 1930s America.

ARISTOPHANES

Aristophanes was the greatest comic writer of his day.His literary activities covered a period of 40 years .During that time,his sharp wit targeted prominent men,political trends,and social foibles.Of the 40 plays known to be genuine product of his genius , eleven remained for prosperity.But these easily prove that for wit,rollicking homour,invention, and skill in the use of language,Aristophanes has never been surpassed

Less is known about Aristophanes than about his plays. In fact, his plays are the main source of information about him. It was conventional in Old Comedy for the Chorus to speak on behalf of the author during an address called the 'parabasis' and thus some biographical facts can be got 'straight from the horse's mouth', so to speak. However, these facts relate almost entirely to his career as a dramatist and the plays contain few clear and unambiguous clues about his personal beliefs or his private life. He was a comic poet in an age when it was conventional for a poet to assume the role of 'teacher' (didaskalos), and though this specifically referred to his training of the Chorus in rehearsal, it also covered his relationship with the audience as a commentator on significant issues. Aristophanes claimed to be writing for a clever and discerning audience, yet he also declared that 'other times' would judge the audience according to its reception of his plays. He sometimes boasts of his originality as a dramatist yet his plays consistently espouse opposition to radical new influences in Athenian society. He caricatured leading figures in the arts (notably Euripides, whose influence on his own work however he once begrudgingly acknowledged), in politics (especially the populist Cleon), and in philosophy/religion (where Socrates was the most obvious target). Such caricatures seem to imply that Aristophanes was an old-fashioned conservative, yet that view of him leads to contradictions.

The writing of plays was a craft that could be handed down from father to son, and it has been argued that Aristophanes produced plays mainly to entertain the audience and to win prestigious competitions. The plays were written for production at the great dramatic festivals of Athens, the Lenaia and City Dionysia, where they were judged and awarded places relative to the works of other comic dramatists. An elaborate series of lotteries, designed to prevent prejudice and corruption, reduced the voting judges at the City Dionysia to just five in number. These judges probably reflected the mood of the audiences .yet there is much uncertainty about the composition of those audiences. They were certainly huge, with seating for at least 10 000 at the Theatre of Dionysus, but it is not certain that they were a representative sample of the Athenian citizenry. The day's program at the City Dionysia for example was crowded, with three tragedies and a 'satyr' play ahead of the comedy, and it is possible that many of the poorer citizens (typically the main supporters of demagogues like Cleon) occupied the festival holiday with other pursuits. The conservative views expressed in the plays might therefore reflect the attitudes of a dominant group in an unrepresentative audience. The production process might also have influenced the views expressed in the plays. Throughout most of Aristophanes' career, the Chorus was essential to a play's success and it was recruited and funded by a choregus, a wealthy citizen appointed to the task by one of the archons. A choregus could regard his personal expenditure on the Chorus as a civic duty and a public honour, but Aristophanes showed in The Knights that wealthy citizens could regard civic responsibilities as punishment imposed on them by demagogues and populists like Cleon. Thus the political conservatism of the plays might reflect the views of the wealthiest section of society, on whose generosity comic dramatists depended for the success of their plays.

When Aristophanes' first play The Banqueters was produced, Athens was an ambitious, imperial power and The Peloponnesian War was only in its fourth year. His plays often express pride in the achievement of the older generation (the victors at Marathon) yet they are not jingoistic and they are staunchly opposed to the war with Sparta. The plays are particularly scathing in criticism of war profiteers, among whom populists such as Cleon figure prominently.By the time his last play was produced (around 386 BC) Athens had been defeated in war, its empire had been dismantled and it had undergone a transformation from the political to the intellectual centre of Greece. Aristophanes was part of this transformation and he shared in the intellectual fashions of the period — the structure of his plays evolves from Old Comedy until, in his last surviving play, Wealth II, it more closely resembles New Comedy. However it is uncertain whether he led or merely responded to changes in audience expectations.

Aristophanes won second prize at the City Dionysia in 427 BC with his first play The Banqueters (now lost). He won first prize there with his next play, The Babylonians (also now lost). It was usual for foreign dignitaries to attend the City Dionysia, and The Babylonians caused some embarrassment for the Athenian authorities since it depicted the cities of the Athenian League as slaves grinding at a mill. Some influential citizens, notably Cleon, reviled the play as slander against the polis and possibly took legal action against the author. The details of the trial are unrecorded but, speaking through the hero of his third play The Acharnians (staged at the Lenaia, where there were few or no foreign dignitaries), the poet carefully distinguishes between the polis and the real targets of his acerbic wit:

ἡμῶν γὰρ ἄνδρες, κοὐχὶ τὴν πόλιν λέγω,

μέμνησθε τοῦθ᾽ ὅτι οὐχὶ τὴν πόλιν λέγω,

ἀλλ᾽ ἀνδράρια μοχθηρά, παρακεκομμένα...

People among us, and I don't mean the polis,

Remember this — I don't mean the polis -

But wicked little men of a counterfeit kind....

Aristophanes repeatedly savages Cleon in his later plays. But these satirical diatribes appear to have had no effect on Cleon's political career — a few weeks after the performance of The Knights, a play full of anti-Cleon jokes, Cleon was elected to the prestigious board of ten generals. Cleon also seems to have had no real power to limit or control Aristophanes: the caricatures of him continued up to and even beyond his death.

In the absence of clear biographical facts about Aristophanes, scholars make educated guesses based on interpretation of the language in the plays. Inscriptions and summaries or comments by Hellenistic and Byzantine scholars can also provide useful clues. We know however from a combination of these sources, and especially from comments in The Knights and The Clouds, that Aristophanes' first three plays were not directed by him — they were instead directed by Callistratus and Philoneides, an arrangement that seemed to suit Aristophanes since he appears to have used these same directors in many later plays as well (Philoneides for example later directed The Frogs and he was also credited, perhaps wrongly, with directing The Wasps.) Aristophanes's use of directors complicates our reliance on the plays as sources of biographical information since apparent self-references might have been made on behalf of his directors instead. Thus for example a statement by the chorus in The Acharnians[38] seems to indicate that the 'poet' had a close, personal association with the island of Aegina, yet the terms 'poet' (poietes) and 'director' (didaskalos) are often interchangeable since dramatic poets usually directed their own plays and therefore the reference in the play could be either to Aristophanes or Callistratus. Similarly, the hero in The Acharnians complains about Cleon "dragging me into court" over "last year's play" but here again it is not clear if this was said on behalf of Aristophanes or Callistratus, either of whom might have been prosecuted by Cleon.